“The Song of Narayama” is a Japanese film of extraordinary magnificence and exquisite cunning, recounting an account of surprising brutality. What a space it opens up between its beginnings in the kabuki style and its subject of starvation in a mountain town! The town implements a practice of conveying the individuals who have arrived at the age of 70 up the side of mountain and leaving them there to pass on from openness.

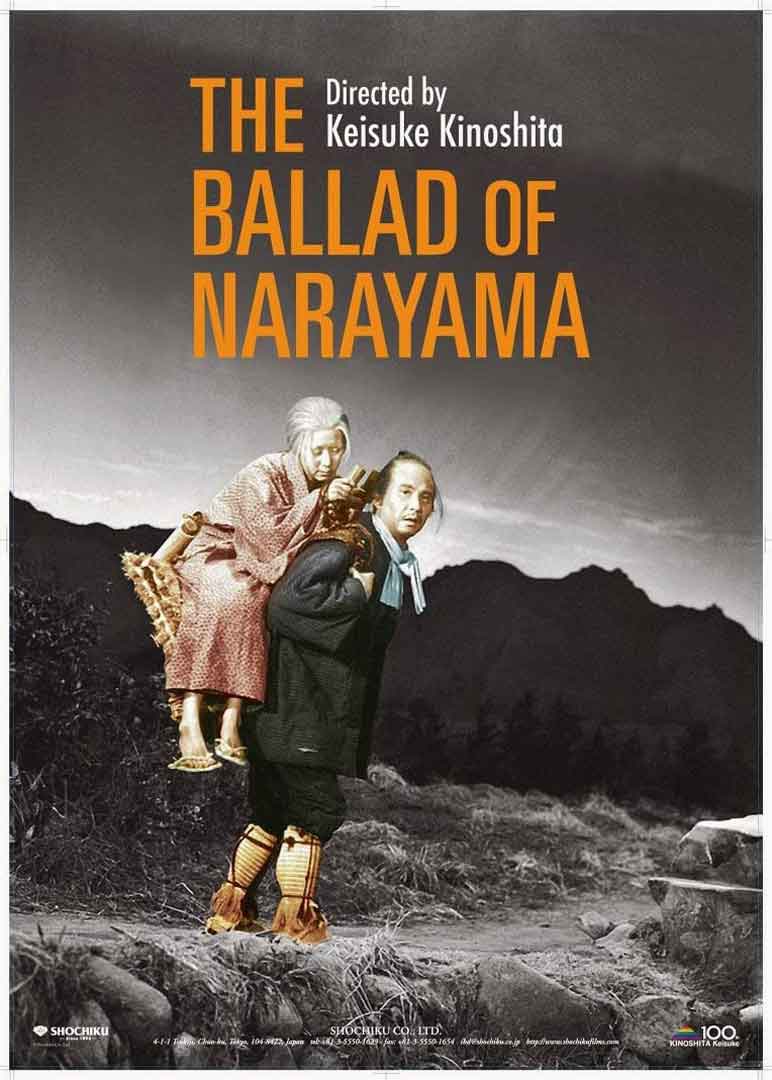

Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1958 film recounts its story with conscious stratagem, utilizing an intricate set with a way close to a percolating creek, matte canvases for the foundations, fog on dewey nights, and lighting that drops the foundations to dark at emotional minutes and afterward raises reasonable lighting once more. A portion of its outsides utilize dark forefronts and horrendous red skies; others use grays and blues. As in kabuki theater, there is a dark clad storyteller to let us know what’s going on.

This stratagem upholds a story that contains extraordinary close to home charge. Kinuyo Tanaka plays Orin, a 70-year-old widow whose renunciation despite her conventional destiny is as a conspicuous difference with the way of behaving of her neighbor Mata (Seiji Miyaguchi), who fights his predetermination. Their family mentalities are correspondingly against; while Orin’s child Tatsuhei (Teiji Takahashi) loves his mom and genuinely wants to convey her up the mountainside, Mata’s family has previously removed his food, and he meanders the town as a frantic scrounger; Orin welcomes him in and offers him a bowl of rice, which be eats ravenously.

Interestingly, with her renunciation and her child’s hesitance to complete her sentence, Orin’s despicable grandson Kesakichi (Danshi Ichikawa) can hardly stand by to be finished with the elderly person, and starts singing a tune deriding the way that she holds, at 70, every one of the 33 of her unique teeth. This is taken up by the townspeople, who emerge as a malevolent ensemble, their tune suggesting she kept her teeth in view of an arrangement with devils. Anxious to fit the bill for her destruction, Orin clamps down unforgiving with a stone and when they see her again her mouth uncovers ridiculous stumps.

This brutal symbolism appears differently in relation to how the film is organized around routine. In spite of the fact that introduced in the kabuki style, it did not depend on a real kabuki play however on a book. Kinoshita is right, I accept, in introducing his story in this adapted way; his structure permits it to turn out to be more tale than account, and consequently more endurable.

His sets and backgrounds reflect he changing seasons with lavish magnificence: Spring, summer, the red leaves of harvest time, then, at that point, the snowy snows on the inclines of Narayama. On the peak, blackbirds roost on frigid precipices as the camera utilizes parallel moves to clear across the barren scene. At last keeping his mom in a vacant put on the mountain, Tatsuhei welcomes the snow with alleviation: She will freeze all the more rapidly. This he can sing just to himself, in light of the fact that the excursion up the mountain has three severe mourns: (1) you should not talk in the wake of firing up Narayama; (2) be certain nobody sees you leave in the first part of the day; (3) won’t ever think back. His adherence is conversely, with the undertakings of the unfortunate neighbor Mata, who shows up not long after bound head and foot, hauled fighting by his child (“Don’t do this!”).

Orin’s decency and acquiescence are at the focal point of the story. In particuar, notice her caring greeting for Tama (Yuko Mochizuki), a 40-year-old widow she has concluded will be the best new spouse for her single man child. Known for her capacity to get trout when no other person can, she drives Tama through the timberland on a hazy evening and uncovers a mystery place underneath a stone in the stream where a trout is consistently to be found. This mystery was never uncovered to her most memorable little girl in-regulation. She even needs to bite the dust before her most memorable grandkid shows up. She needs to free the town from an eager mouth.

Some will find Orin’s way of behaving bizarre. So it is. Maybe, in the years not long after The Second Great War, she is planned in recognition of the Japanese capacity to introduce acknowledgment even with the horrifying. You can append any arrangement of equals to Kinoshite’s illustration and make them work, however that appears to fit.

Keisuke Kinoshita (1912-1998) is of a similar age as Akira Kurosawa. Saying that thoughts sprang rapidly into his psyche, he moved among periods and classes, and made 42 movies in the initial 23 years of his profession. He was quickly drawn to movies; a film was shot in his old neighborhood when he was in secondary school and he took off to a studio in Kyoto. His family made him get back, however later dropped its resistance to his profession plans. Without an advanced degree, he began submissively as a set photographic artist, and moved gradually up, sending in an endless flow of screenplays to the studio boss.

He made shows, musicals, thrill rides, musicals, anything, yet he never made another film like “The Melody of Narayama.” In its obvious truth juxtaposition of destiny and workmanship, it has a permanent impression. Tatsuhei’s second lady of the hour Tama tells him: “When we turn 70, we’ll go together up Narayama.”

Leave a Reply