D.H. Lawrence’s novel doesn’t begin with plot focuses or scene-setting. Goodness, no. In the initial passage, Lawrence roars into a bull horn: “Our own is basically a terrible age, so we won’t take it sadly. The disaster has occurred, we are among the remnants, and we begin to develop new little natural surroundings, to have new little expectations. It is fairly difficult work: there is currently no smooth street into what’s in store: yet we go round, or scramble over the obstructions. We must live, regardless of the number of skies that have fallen.” Written in the outcome of WWI, with Europe in ruins, this section was in a real sense “words to live by.”

To say it another way, Woman Chatterley’s Darling isn’t simply a provocative romantic tale. Indeed, there is hot disloyalty however the genuine point (which was lost in the resulting long term outrage encompassing the book) is coordinating body and psyche as an approach to reconnecting to our most flawless driving forces, and in this manner, perhaps mending the entire world. Lawrence wore his Thomas-Solid Walt-Whitman impacts on his sleeve. Obviously, by the day’s end, the explanation the book scandalized ages was a direct result of all that pulsating beating sex, that multitude of rising organs and cryptic liquids, the Edenic climaxes, in addition to several f-bombs (utilized as action words, not descriptors, a urgent differentiation).

Lawrence’s book has been adjusted for screens of all shapes and sizes ordinarily, to differing levels of progress. The plot is notable and isn’t exactly unique (a rich lady connects with her masculine grounds-keeper), and there are landmines wherever in the material. On the off chance that a variation simply centers around the hot sex, then you’re missing what Lawrence was getting at the “calamity” of war, the risks of industrialization, the developing class struggle, and the horde ways humankind has experienced in a profound sense focusing on mind over body. This new transformation, coordinated by Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, evades the landmines astoundingly well. The film shines and inhales, leaving space for revelation.

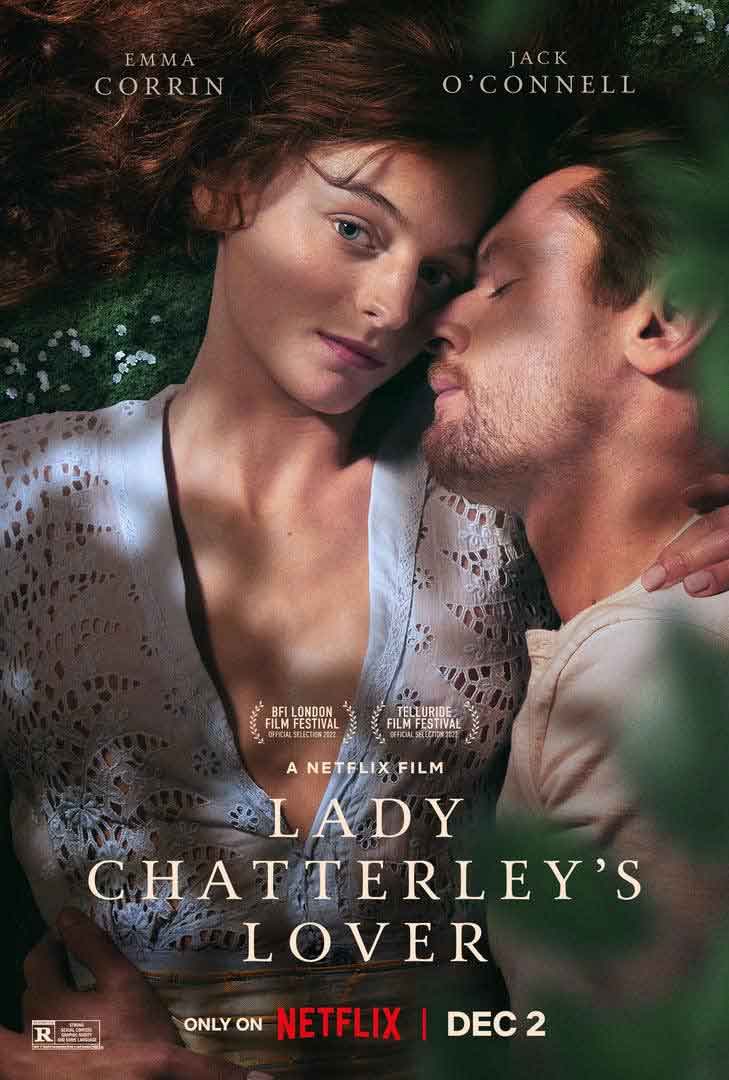

Connie Reid (Emma Corrin) has several affection illicit relationships added to her repertoire when she weds Baronet Clifford Chatterley (Matthew Duckett), just before he takes off to battle in the Incomparable Conflict. Connie was brought up in an unassuming marginally bohemian family, so becoming “Woman Chatterley” is a gigantic change. She is taken out from London, from her sister Hilda (Faye Marsay), to live in the enormous Chatterley bequest. At the point when Clifford gets back from the conflict, he is deadened starting from the waist and needs full-time care. Connie loves him and gives her all. In any case, she’s a young lady with a feeble spouse who shows no interest in becoming imaginative about sexual joy. He needs a main beneficiary however, so he proposes she take on a sweetheart, not really for delight, obviously, but rather for impregnation. Connie is crushed. She’s hurting for warmth and contact. Then she gets a brief look at Oliver Mellors, the gamekeeper (Jack O’Connell).

Furthermore, with scarcely about six words verbally expressed between them, they attach. He isn’t the attacker or initiator. She is. He is more aware of the class distinction than she is. He refers to her as “m’lady” in a tone of profound regard and struggles with dropping it after they’ve been personal. Class mindfulness is engrained in him. In a flash, the relationship has warmed up so much that Connie’s hours-long “strolls” could stimulate doubt. Clifford invests the majority of his energy with business partners, examining the fights ejecting in the mines in their region. (A reverberation of Lawrence’s interests about the harming impacts of the Modern Upheaval is available.) Clifford probably won’t see that something is happening with his better half, however Clifford’s medical attendant house keeper Mrs. Bolton (Joely Richardson) absolutely does. Her alarm looks at Connie’s rumpled hair and shining cheeks flash the film with fear about what will happen when this relationship is uncovered, on account obviously it should be uncovered.

With a screenplay by David Magee (“Tracking down Neverland,” “Life of Pi”), “Woman Chatterley’s Darling” takes as much time as necessary with this. The darlings might have intercourse very quickly, yet from that point forward, they’re on a way of disclosure. Sex isn’t simply sex, and this is one of the principal achievements of Clermont-Tonnerre’s touchy and, surprisingly, sensitive methodology, as well as the transparency of Corrin and O’Connell. We live in a second where adult sex has essentially evaporated from the cinema.

There was a major Twitter “conversation” when about simulated intercourses, and a few group concurred that intimate moments were possibly OK “assuming they advance the plot.” That ought to profoundly shock “Don’t Look Now.” Individuals don’t engage in sexual relations to propel the plot. Sex is a major piece of many individuals’ lives. In “Woman Chatterley’s Darling,” the sex isn’t conventional. It is intended for these two individuals, and the particularity makes it sensual. You don’t understand how intriguing something like this is until you see it gotten along admirably.

The film was shot with a mercury newness by Benoît Delhomme. There are no masterful shots; there isn’t anything formal or slow. All things being equal, there’s heaps of handheld camera work, bunches of focal point flares, and the camera pursuing Connie as she bounces across the green fields. The forest where Connie and Oliver get together are a primitive woods, where all that — even the light — has a material quality. Isabella Summers’ score improves feelings as opposed to underlining them.

Both Corrin and O’Connell are sublime here. Connie and Oliver have been battling submerged for their entire lives, and they didn’t understand it until they met. Now that they’ve met, they can at last relax. The manner in which Corrin and O’Connell gradually open dependent upon one another, you can see the relationship extending under their feet with each second. This requires such receptiveness and availability on the entertainers’ parts. Something as chatterley “Woman’s” Darling requires the crowd to be on the sweethearts’ side, regardless of whether what the sweethearts are doing is off-base. In the event that it’s an ill-fated love, similar to Ilsa’s and Rick’s in “Casablanca,” you need to “purchase in” to their association, and sob when it can’t be. In “Woman Chatterley’s Darling,” appalling tattle begins to spread, and it’s agonizing to consider Connie and Oliver’s Eden being ruined. This is expected primarily to Corrin and O’Connell’s amazing open work with each other.

“Woman Chatterley’s Darling” is Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s subsequent component. Her most memorable film was in 2019’s “Horse,” featuring Matthias Schoenaerts as a jail prisoner partaking in a recovery program including the restraining of wild colts. “Horse” was one of the unlikely treasures of 2019, with Schoenaerts giving an incredible execution as a vicious man loaded up with disgrace about his brutal past. “Bronco” has a similar material quality as “Woman Chatterley’s Darling,” and a similar happening continuously energy. You believe you are running close by the characters, attempting to find them on their processes forward. “Colt” was a lot more modest film than “Woman Chatterley’s Darling,” despite the fact that it had a few extremely confounded components, similar to that large number of wild broncos. Clermont-Tonnerre handles the undeniably more aggressive “Woman Chatterley’s Sweetheart” with certainty and alive-ness, and assuming the film loosens a smidgen when the blabber-mouthy walls-shutting in scenes start, it doesn’t detract from the headliner: Corrin and O’Connell, lying on the grass in the timberland, their bodies pale against the thick green, breathing as one. It’s subtly significant.

In 1925, Lawrence expressed, “Whoever peruses me will be in the main part of the scrimmage, and on the off chance that he could do without it — assuming that he needs a protected seat in the crowd — let him read another person.” Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, Emma Corrin, Jack O’Connell, the entire cast and group, puts us “in the main part of the scrimmage.” You could lose all sense of direction in there and never emerge.

Leave a Reply